(click to enlarge photos)

Waiting on the front lawn of his studio at 817 Second Avenue, we imagine that pioneer photographer Theo. Peiser arranged with Andrew Charleston, Herman Norden and/or Martin Gunderson, all officers of the Lake Union Furniture Manufacturing Company, to pause and pose with their float here two lots south of Marion Street. The San Franciscan Peiser reached Seattle in 1883 and soon set up his studio on Second. Most of his sign appears on the left.

In booming Seattle there was then plenty of work for a photographer with Peiser’s hustle. Of his four local competitors David Judkins was also on Second and so close by that Peiser advised the readers of his full page advertisement in the 1887 Polk City Directory, “Be sure to read the sign before you enter, so as not to make any mistake and get into another gallery. Peiser’s is the only one with the title ‘Art Studio.’ Please bear this in mind.” Peiser’s ad is so “arty” that is features a fourteen-verse poem extolling Seattle, its surrounds and his studio. The last verse reads, “Eight hundred and seventeen, Second Street, Theo E. Peiser’s Art Studio neat. His work, view and portrait, can’t be beat – On the continent.” (Click the poem directly below to enlarge it.)

Lake Union Furniture ran its own full-page ad in 1888, the first one in that year’s city directory. As on their float, the partners promoted themselves as “a deserving home industry” with furniture “for furnishing the cottage as well as the palace.” While the manufacturer’s plant was on the south shore of Lake Union, their primary saleroom was at Second and Yesler (Mill Street), which put it in the way of the city’s “Great Fire” of June 6, 1889. Peiser and all of his competitors’ studios were also consumed. Before the fire he had proudly noted, “every negative was preserved.” No longer; all his glass plates with local scenes and paid portraits were broken and scorched. Distraught, he moved to Hood Canal.

WEB EXTRAS

Anything to add, Paul?

Yea Jean, a few things relating to Peiser and/or the neighborhood near Marion and 2nd. I’ll put it up, but probably wait with corrections until Sunday morning – late.

PEISER’S ART STUDIO

(First appeared in Pacific, August 9, 1987)

When Theodore Peiser came to Seattle in 1883, the San Francisco native set up his studio one lot south of Marion Street on the west side of Second Avenue. But, like most other local photographers, Peiser did not always stay in town. Peiser advertised “A large stock of Washington Territory views” on his street-facing facade of is rough studio building on Second Avenue. The accompanying photo also shows his “Traveling Studio” – a tent – next “door” to the south. Apparently the photographer rolled up part of the tent roof, to use the sun as the light source for exposing contact prints when working in the “field” or even, as here, three lots south of Marion.

Typical of photographers of his day, Peiser liked to consider himself an artist. Photography was then still young and promoted itself as a kind of “painting with light.” They were eager to borrow some of the romantic distinction residing in the fine arts. It was a grab for the glamour that did not attach directly to the job of merely making images with the aid of optics and chemicals. In the smaller type between his main sign and the montage of selective views he fixed to the front of his studio, Peiser promised “First class work guaranteed in any weather.”

Peiser could handle the weather, but not Seattle’s Great Fire of 1889. Of the roughly 33 city blocks destroyed, his was included, and it nearly wiped him out. It was a loss for both Peiser and the photographic memory of Seattle, for what survives of his work from the 1880s is still one of the more significant records of the city’s growth in that explosive decade. Here are a few examples, concluding with a self-portrait that recently surfaced through the good services of Dan Kerlee and Ron Edge.

It the exceedingly useful Seattle Times on-line archive that is wonderfully word-searchable (get out your library cards) for all subjects that appeared in the Times between 1900 and 1984, Peiser first appears with the first clip attached below, a snipped – and snippy – classified ad directed to a target in far off Seattle. Peiser makes his post from San Francisco. We do not, however, learn if Peiser determined if Lewis Ericckson was an “honest man” after his return to Seattle. If he was, would Ericckson then insist that Peiser run a second classified in The Times indicating that “Honestly Ericckson you are an honest man, and I never expected any other.”

Late in 1904 Peiser advertizes for a cheap room to rent and in that context also indicates a desire to sell his photography equipment. Next in 1906 (below) he looks for a farm, still has his photo gear and still wants to sell it. And he is addressed in the Eitel Building at the northwest corner of Second and Pike. It is still there.

On the tenth of March, 1907 the Seattle Times reports on the photographer’s poor health.

Less than three weeks later The Times reports again on Peiser’s health, and this time his complaints as well. Peiser is living in the East Green Lake neighborhood at this time.

Later that year, 1907, or the next Theo. Peiser does make it back to California. Born in 1853, he dies in 1922 – 69 years and before antibiotics or asthma sprays. Finally (for us), Peiser and his studio are remembered in 1922 with The Seattle Times then popular – and probably first – series on local historical photography, called . . .

=====

What follows first appeared in Pacific on January 24, 2004. In the first photo above – at the top of this day’s blog – part of the south facade of the Stetson Post Building facing Marion Street appears in the upper-left corner. That apartment house survived the 1889 fire and much else. Here, below, we see it still holding its place at the northeast corner of Second Ave. and Marion Street. (Historical photo courtesy of Lawton Gowey)

One century – plus a year or two – separates these views looking north on Second Avenue through its intersection with Marion Street.

MARION STREET REMINDERS

(First appeared in Pacific, January 2004)

Only one feature survives between this “then and now” and it has been truncated. On the right of the contemporary view five of the original seven floors of the Marion Building have been lopped away at the southeast corner of Marion Street and Second Avenue. But while humbled on top, at the sidewalk the building now boasts a stone façade with monumental pillars. Somewhat early in its now more than century-long life the first floor was altered for a bank, the long since merged and folded National City Bank.

The Webster and Stevens negative number for this (two pixs above) look north up Second Avenue is 665. That’s an early number for the studio that was the principal supplier of photographs for The Seattle Times during the first quarter of the 20th Century.

Besides the red brick gloss of Second Avenue, the illustrative intention of the photograph may be to contrast the two showy structures that look at one another from the north corners with Marion Street. On the right is the Victorian clapboard Stetson-Post Building with the central tower. It was built in 1883, curiously only six years before the ornate brick and stone Burke Building on the left was raised above the ashes of the city’s “Great Fire” of 1889.

When new, locals considered the Burke Block our best example of the latest design in business blocks. When old, the Burke Building was mourned by many as it was replaced in 1974 with the Henry M. Jackson Federal Office Building. In the 1880s Thomas Burke, its namesake, had been a resident in the Stetson Post Building that was saved from the fire by the generous width of Second Avenue and the vigorous reapplication of wet blankets to its steaming skin.

While it appears to be an antique, the Stetson-Post has only reached its mid-life here (Six photos up). On August 10, 1919 The Seattle Times noted its passing, describing it as “Second Avenue’s last pioneer landmark.” By then it was an outstanding anomaly on Seattle’s most modern street. Lined with skyscrapers like the Smith Tower (1914), the Hoge Building (1911) and the New Washington Hotel (1908) Second Avenue was our first “urban canyon.”

=======

AYPE WELCOME ARCH, 2nd & MARION, 1909

(First appeared in Pacific, May 18, 1997)

Four days before the Alaska Yukon Pacific Exposition’s opening on June 1, 1909, on the University of Washington campus, locals were excited by a published sketch of a commemorative arch that Vancouver, B.C., planned to erect at Third and Marion. Seattle Mayor John Miller announced that he “regretted in view of Vancouver’s enterprise that Seattle had not seen fit to build an arch.”

City superintendent of buildings Francis W. Grant quickly plucked an arch design from architect W.M. Somervell for the mayor to wave at the City Council. One councilman, future Mayor Hiram Gill, declined; the 17 others agreed, including T.P. Revel, who appealed to the powerful political motive of shame – or its avoidance. Revel noted that he did “not favor the expenditure of funds for gilt and tinsel as a rule, but I will vote for this bill since it is apparent that Seattle must maintain its own reputation.” Grant lamented that the proposed $4,000 would put Seattle at a disadvantage in what he said should be a race with Vancouver to complete the monuments. The council raised the investment to $6,900 but declined to treat the building as a contest.

Seattle’s completed arch over Second Avenue at Marion was “unveiled” July 21, one day after state Superior Court Judge J.T. Ronald denied an injunction by local labor unions to stop construction on the grounds it was contracted without bids and built with non-union labor. Ronald, a former Seattle mayor, reasoned that the city could build whatever street ornaments it wanted so long as they were not as ephemeral as fireworks or flags.

What Seattle got was, at least, flag-like: a welcome banner strung between two 85-foot-tall columns. After dark the two braziers at the top emitted smoke-like steam illuminated by fire-red lights. These burning pots were copper green, and the columns were an old~ivory tint.

The enthusiastic mayor joyfully announced, “I’d like to see Seattle smothered in bunting.”

=======

DAD’S DAY

(First appeared in Pacific, June 15, 1986)

The banner being marched down the middle of Second Avenue in the parade scene above reads: “Every Dad That Don’t Tum Out Is a Coward.” And what might that dad be afraid of? Mom, of course!

So, on Thursday, July 17,1913, near the start of the Golden Potlatch, Seattle’s third annual summer festival, mayor and “dad”, George F. Cotterill pleaded with the city’s mothers through a mayoral proclamation “calling upon the bosses of the dads to give ‘them a holiday’,” and to encourage them to promenade on Saturday afternoon in the Dad’s Day Parade.

Some of the city’s mothers responded by putting down their rolling pins and handing their aprons and brooms to the dads: In the foreground of the photo are fathers dressed in kitchen drag and wearing signs that say “I’m a Dad.” This is just the start of the procession. Behind them are floats, which depicted “Dad doing the family washing, dad on ironing day, dad washing the dinner dishes, dad hooking up mother who was about to go out to a theater party . . . and dad in every other form of servitude, which the downtrodden declared had been suffered too long.” according to a Seattle Times article.

The dads’ floats were donated by dad-owned local businesses (It was the only 1913 Potlatch event that didn’t cost the city an extra cent.), with the omnipresent “Your Credit is Always Good” Standard Furniture float the best among them. Herbert ‘Schoenfeld, the founder of Standard Furniture [In 1896, at least, still the Schoenfeld Furniture in Tacoma], was the originator and chairman of Seattle’s first “Dad’s Day.”

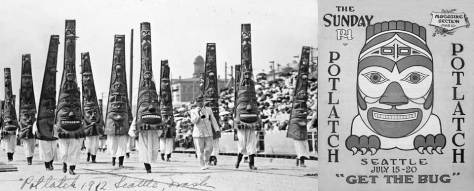

But the dads didn’t entirely take over the summer event. Waving above this parades scenes, on the right, is the Potlatch Bug. The Potlatch name was taken from a Northwest native ritual during which fortunes were given away in exchange for prestige. Ed Brotze was The Seattle Times artist who designed the Potlatch bug as a somewhat primitive amalgam of a totem-pole figure and a native mask. And the most popular Golden Potlatch costumes were not aprons and bonnets, but traditional dress of old sourdoughs and Indians – with variations.

========

PARADE of ALL NATIONS

(First appeared in Pacific, Oct. 21, 1984)

William the Duke of Proclamations pronounced six of them (proclamations) for Seattle’s first summer festival, the 1911 Golden Potlatch. The first was: “Forget dull care and remember that this is the time for INNOCENT AMUSEMENT.”

Recently [in 1984], two albums stuffed with photographs of these amusements have surfaced from the other Seattle underground of lost or forgotten images. This view of the Afro-American float in the Potlatch’s Parade of All Nations is one of them. On July 21 , 1911, The Post Intelligencer’s review of this spectacle was headlined, “PARADE OF ALL NATIONS IS SEEN BY GREAT CROWDS . . . Cooler Day Brings Out Throng For Racial And Industrial Pageant.” The article below the headline listed the “races.”

“After the Japanese Lantern Float, the Cle Elum band led the Italian section. Prominent Italian citizens and their families rode in gaily-decorated automobiles. Then followed the Chinese in automobiles and after them an Afro-American float, which won much applause. The Indians followed . . . ” Or Europeans dressed like them – it was not very difficult to tell them apart.

The Golden Potlatch was a local creation hybridized from Seattle’s enduring fixation with the 1897 Alaska Gold Rush (hence, the “97 Seattle” pennants on the float), and the white man’s fascination with the Indian’s ritual of gift-giving called the potlatch. In this spirit, another fair spokesperson, a Reverend Major, advised all citizens to give the gift of “good cheer because it tears down the walls built between us.” The clergyman advised that the Parade of All Nations would show how “Every citizen of Seattle is interested in every other citizen . . . We are a big family.”

Wisely, Seattle’s Black community arranged their float with girls – the human representatives with the best chance of escaping the grown-up anxieties of racial prejudice. Of course, the reality that awaited them at the end of the parade was the double discrimination held for both black and female. They could return to the love of their own families, but the “big family” would return to making it very hard for them to become anything other than housemaids, nursemaids, cooks, charwomen, or mothers.

Esther Mumford, in her excellent history, Seattle’s Black Victorians, notes that “Most of the women never realized their importance . . . Regardless of their marital status, they were at the bottom of society, often poor and ignorant, but it was from that position that women served to undergird the black community by maintaining its basic unit, the family.”

Racial discrimination in Seattle was more pernicious in 1911 than it is today. But it’s here, and there is still “bad cheer” to dispel if we are at last to respond to William the Duke’s sixth and final proclamation: “Apply the Golden Rule to the Golden Potlatch and you will do wrong to no man.” Or woman.

===========

KNIGHT TEMPLARS ARCH, 2nd & MARION, 1925

(First appeared in Pacific, March 18, 1984)

The last week of July in 1925 was outstanding for Second Avenue. To hail a parade of 30,000 marching Knight Templars, Second Avenue wore hundreds of illuminated banners and wreaths, some 700 flaming torch globes and the smile of a welcome arch six stories high.

The Knight Templars, a masonic order modeled after Medieval Christian Crusaders, were attending their 36th triennial conclave. And since their principal symbol is the Christian cross, for this one summer week in 1925, Seattle, the host, was filled with crosses. The Knights’ committee, with help from a contracted General Electric Company, put a four-story illuminated and bejeweled cross atop, the then brand new Olympic Hotel, lined the streets with another 155 illuminated passion crosses and “crossed” the sky with 12 searchlights. The Grand Welcome Arch at Marion Street was topped at 95 feet with its own flood-lit cross. It was an sensational and for some enchanting light show.

But it was also Second Avenue’s last hurrah.

Second Avenue was distinguished from other downtown streets when Seattle’s first steel-girder skyscraper, the Alaska Building, was erected in 1904 at the southeast comer of Second and Cherry Street. The avenue was on its way to becoming the city’s center-stripe of grand-style urbanity, its main canyon of glass, terra cotta and granite. In 1908 the New Washington Hotel (now the Josephinum) was completed and stood as the northern pole for this 12-block belt of hotels, banks and department stores. After 1913, the 42-story Smith Tower was Second Avenue’s southern summit.

By 1926, the year following the Templar visit, Second Avenue’s reputation as a bustling strip was beginning to be ecliopsed by major development plans for higher avenues. Henry Broderick, the long-lived real estate hustler, prepared for the press a map locating the 37 downtown buildings that were either underway or projected for early construction that year. They represented an investment of $25 million – a Seattle record. Ten were slated for Third Avenue, four for Fifth Avenue and five on Sixth, and most were closer to Westlake and the new retail north end than to the pioneer south end and Yesler Way. Only one of the buildings was listed for Second Avenue.